https://er.educause.edu/articles/2015/3/engaging-faculty-in-online-education

Key Takeaways

- By drawing on direct experience, facilitating learning from peers, and exploring engagement practices, Brown University's online development team is creating an online learning "adoption wave" among faculty.

- The online development team continues to introduce ways of helping faculty and senior administrators more fully understand and expand on the opportunities online learning presents.

- An institution steeped in the traditions of residential education and initially dubious of online education now builds on its early success with online learning.

Karen Sibley, Vice President of Strategic Initiatives and Dean, School of Professional Studies, and Ren Whitaker, Director of Online Development, School of Professional Studies, Brown University

The initial resistance to online learning by many institutional leaders has given way to urgency about engaging faculty in online instruction. Even at traditional residential universities and colleges with well-established excellence in seminar, lecture, and lab instruction, experimentation with online learning is rampant as institutions rush to adopt educational technology and online pedagogy. Administrators may urge action, and some faculty view exploring online teaching and learning as an inviting and even invigorating challenge, but others still decline to participate. Many faculty have yet to use technology in their instruction — even something as basic as the campus learning management system — much less experiment with flipped or hybrid classes. This leaves many IT, ed tech, and online learning professionals challenged to move their institutions and faculty online and into the 21st century of education.

Because mandates rarely succeed in the higher education culture, finding ways to ease the pedagogical transition for inexperienced, curious, and even reluctant faculty members is critical. Those professionals charged with introducing and implementing online education must give faculty the opportunity to better understand, explore, experience, critique, and ultimately accept or reject this form of pedagogy.

Institutional Support: Incentives

With knowledge of the salient research evidence and familiarity with the concepts of online learning, faculty members can understand its value to students. Asynchronous online learning provides students more time and flexibility for class participation, and it enables reflection and thoughtful engagement while allowing students to meet personal and professional obligations. Well-designed and executed online courses can provide an engaging, resource-rich learning environment in which students share their ideas, research, and knowledge with others in a collaborative peer-to-peer learning experience. Students have the opportunity to develop an expanded network of peers, faculty, and experts that brings new information and fresh perspectives to the experience, enhancing the outcomes for both students and faculty.

In contrast to the benefits for students, the advantages for faculty faced with creating and teaching online courses might not be obvious. The time and effort required to use new technology, to plan and develop a course, to work with instructional designers who have little or no knowledge of the academic discipline, and to teach in "new ways" may seem a daunting task and a drain on their time with little potential for reward. Faculty might believe that this time would be better spent in research, writing, and other professional activities that garner higher recognition and reward than teaching.

Institutional leaders can communicate clearly the value added by technology-assisted learning at their institution and how online learning can enhance the student experience, but they need to provide incentives and support to secure faculty participation. Although assessing and reporting institutional benefits and success from online instruction are necessary, they are not always sufficient to influence faculty. Faculty must have evidence of efficacy, access to easy points of entry, confidence in institutional support, and incentives to develop online instructional capacity.

Incentives for faculty to develop knowledge and skills in online learning can include:

- Providing compensation as salary, research funds, or time (e.g., a course buy-out)

- Appealing to a sense of curiosity and a desire to develop new skills for those attracted to experimental work or invigorated by the chance to reimagine their courses

- Delivering training and support to lower the barriers and to decrease the time and effort needed to develop or adapt new instructional approaches

- Activating a sense of mission and loyalty to their students and the institution

- Increasing a sense of relevance for those who want to remain current in the rapidly changing environment of higher education

- Recognizing effective engagement in online learning in the institutional reward systems

Inform and Inspire: Ed Tech and Instructional Design Teams

While early experiments with online learning aimed to enhance brand identity, address the need to remain current, and pursue new revenue sources, technology-mediated instruction has become part of the higher education landscape. Some who witnessed the early days of online education or saw poorly designed online courses might still judge online learning with these outdated or low-quality examples in mind. They may think that online learning consists only of lecture-capture videos and PowerPoint presentations viewed by students at their leisure, followed by online quizzes to test understanding.

"MOOC mania" did much to promote the idea of online learning, but the media's focus on huge enrollments raised criticism of low completion rates — often not an accurate measure of a MOOC's success. Questions about the lack of rigor or low student engagement emerged in qualitative assessments of online instruction, while dreams of lower costs and broader access held quantitative allure.

Those who recognize online education as a specialized discipline that requires time and thoughtful attention believe that some of these initial efforts damaged public perception of online learning by misrepresenting its potential and fostering conclusions that it is of lower quality than traditional classroom learning. Faculty need to recognize it as a distinctly different medium with qualities and advantages of its own.

What can ed tech and online instructional development teams do to clarify what online education is, what it isn't, and what it can be? First, to counteract misperceptions and assumptions, they can provide faculty a more complete, accurate, and realistic picture of what quality design and facilitation look like in online education. By showing faculty examples of well-designed online courses and best practices in online pedagogy, these teams can inspire faculty to experiment with technology-enhanced teaching to produce courses of the highest quality. Next, they should encourage early adopters to share with colleagues their experience working with the design and tech support teams as well as their experience teaching online. This might encourage other faculty to investigate and experiment with online education.

Training and Support

Faculty have expertise in scholarship and in classroom instruction, but for many, online learning remains a new and discomforting area. While faculty rely on technology in their own scholarship, when it comes to teaching, some see technology as standing betweenthem and their students — not as an aid to instruction or a means to connect more effectively with their students. Some feel intimidated or overwhelmed by new learning technologies, or fear that they will appear inept to tech-savvy students or colleagues. Others are offended at "being asked to relearn" how they teach.

Ed tech and online learning professionals can lessen these concerns by listening closely to and working respectfully with faculty to build trust and positive, productive relationships. They should do everything in their power to be seen as a respected, highly skilled, and supportive resource, giving faculty the confidence to ask novice questions or take appropriate risks with their course designs. Mutual trust and respect enable tech and design experts to provide the training and support faculty need.

With time a scarce and valued resource and faculty attention directed to many compelling obligations, online course design and facilitation training must be easy to access and digest. Initial instruction in online pedagogy must focus on the highest-level priorities and skip everything else. Greater understanding and ability can come later, when the faculty member is proficient at the basics and has the confidence and curiosity to further develop their course design and facilitation skills.

Ed tech and online development teams need not reinvent the wheel to develop this kind of training. Many institutions have effective programs, resources, and best practices for online faculty and are happy to share them with colleagues. Borrow before you build whenever possible to save time and effort.

The online development team at Brown University has a highly effective faculty onboarding and development process that is somewhat time intensive initially. To start, an interested (or simply curious) faculty member meets with the director of online development to discuss teaching online, bring up questions and concerns, and explore a course or course concept for possible development.

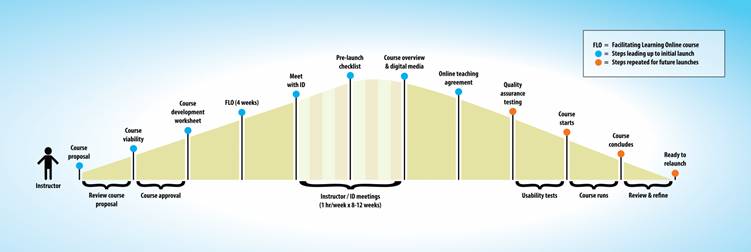

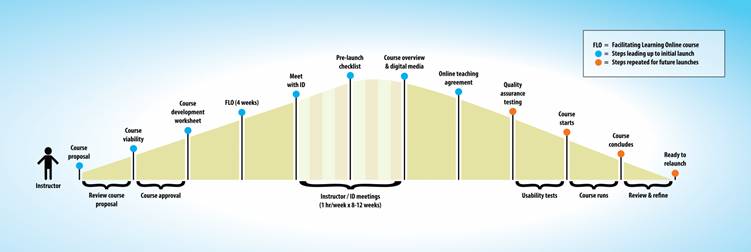

Next, the faculty member is introduced to the Course Development Process Model(figure 1). The model illustrates the key milestones and deliverables involved in online course development and facilitation, as well as what is required from both the faculty member and the design team at each stage. Clarifying the process and expectations right from the start removes any mystery about the process and prepares faculty for the work ahead. During this conversation some faculty members realize they can't devote the time and effort required to develop a course and make an informed decision not to participate — at least at that time. This step can save everyone involved much frustration, time, and effort.

Figure 1. Online course development process, School of Professional Studies, Brown University

Once a faculty member decides to develop an online course, a dedicated instructional designer (ID) is assigned to the project. The ID meets the faculty member on a weekly basis and begins by asking: What excites you about this course? What do your students love about it? By uncovering the instructor's vision and passion for teaching and for the subject matter, the ID can help imbue the course with the instructor's energy and personality and build in points of connection between professor and student.

Whether preparing a new course or redesigning an existing face-to-face course for the online environment, the ID and faculty member discuss the course learning objectives and consider how to accomplish each in the most engaging and effective way. The key questions are: What should students be able to do as a result of this course? What activities or assignments will generate evidence of student understanding and provide the instructor with an effective means of assessment?

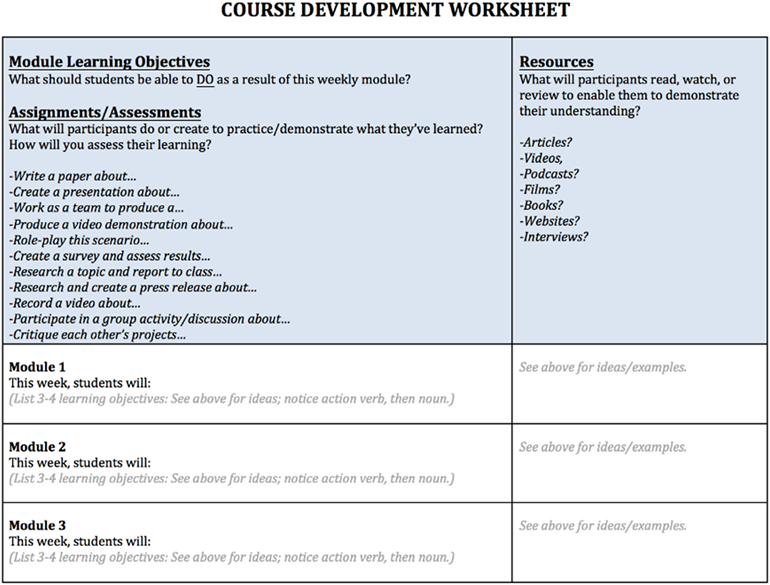

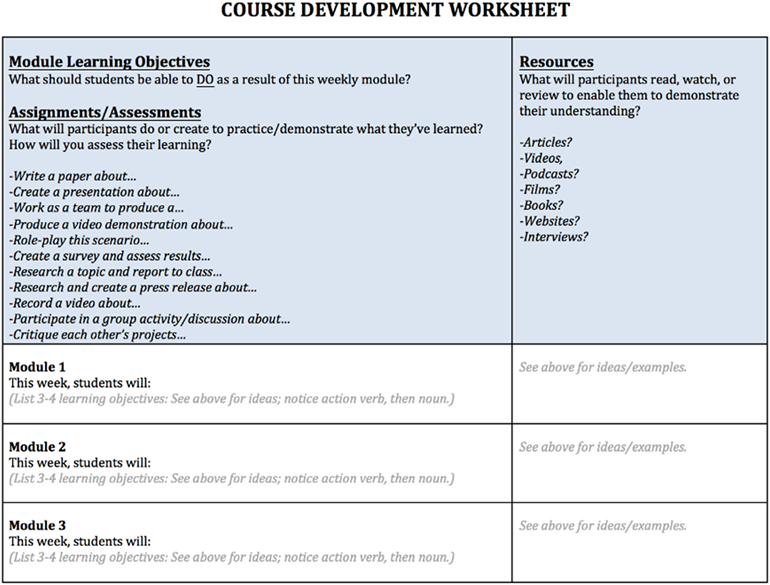

If needed, the ID may introduce the course development worksheet (figure 2) to help the faculty member draft or refine learning objectives. This worksheet prompts faculty to consider different and potentially more meaningful ways to engage and assess student learning while taking full advantage of resources available online.

Figure 2. Online course development worksheet, School of Professional Studies, Brown University

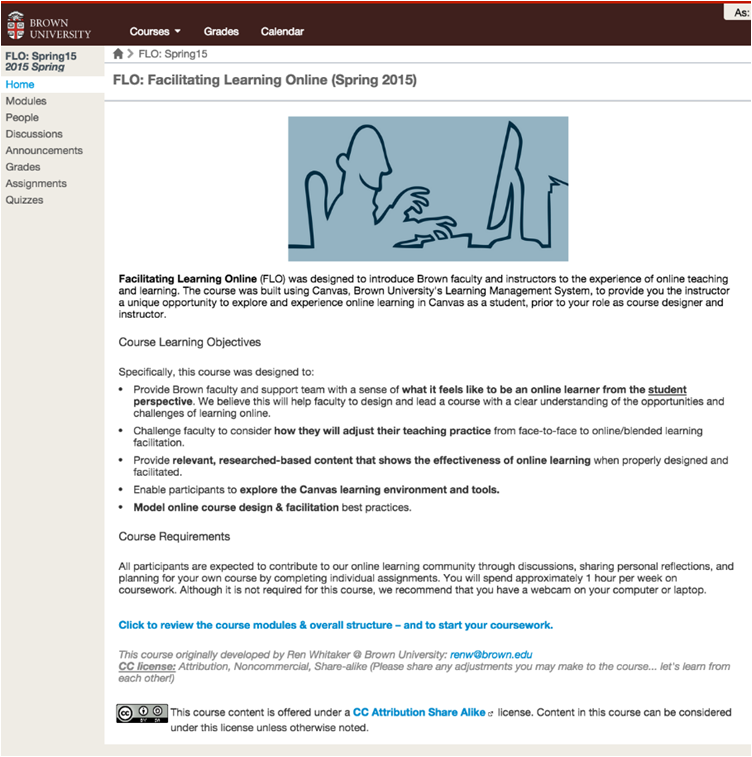

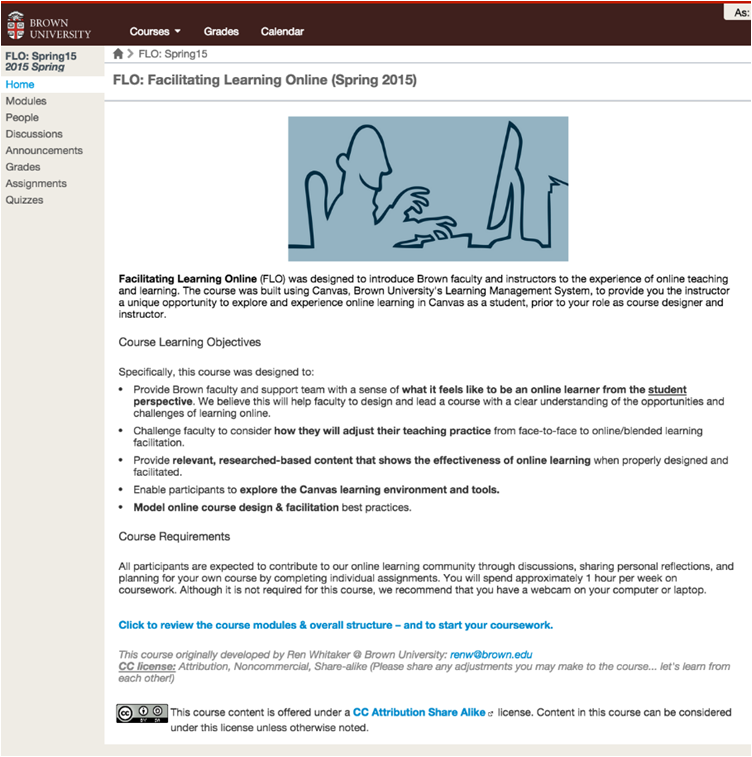

Prior to the start of their courses, faculty who are new to online teaching participate as students in the four-week, fully online course "FLO: Facilitating Learning Online"(figure 3), to experience online learning first-hand. Each week, they spend approximately one hour in FLO exploring the challenges and opportunities presented by online learning. Faculty also become familiar with Canvas, the LMS in which they will ultimately develop and lead their own courses. FLO is asynchronous; faculty participate as a cohort and must keep up with weekly assignments and discussions. Instructional designers lead the course and are quickly recognized as collaborative leaders and skilled pedagogical guides with expertise in online learning. Perhaps most importantly, faculty have the chance to experiment and ask questions about online learning in a low-risk environment and to build new professional relationships with colleagues across campus through the shared online experience.

Figure 3. Opening screen for FLO: Facilitating Learning Online, School of Professional Studies, Brown University

After faculty have completed FLO and fully developed their courses, they receive the Pre-launch Instructor Checklist from their IDs, conduct a final quality check, and resolve any issues before course launch. The checklist encourages faculty to test course functionality and confirms their readiness to facilitate and assess student work using the LMS. Each checklist item connects to an Online Video Tutorial, so faculty can troubleshoot problems on their own whenever possible rather than depending on ID or IT support. This helps build confidence and empowers the faculty members to take ownership of their courses.

The role of the IT, ed tech, and ID professionals does not end when a course launches. As the course runs, particularly in its first iteration, the IT, ID, and ed tech teams respond quickly to the technological snags and unexpected issues that inevitably arise. This not only supports a positive student experience, but it also ensures that faculty feel supported. Their comfort level encourages them to continue teaching online. Even after the course concludes, asking both faculty and students to share their online experience helps guide improvements to the next iteration of each course.

There is no substitute for positive, authentic, front-line experience with quality online education. Faculty who are well-supported by their institution and online learning specialists become the most effective champions for online learning and can address their peers' concerns. At Brown University, the online learning "adoption wave" started with a few interested faculty members who accepted the challenge of teaching online and flourished with support from the university's online learning professionals.

Recommendations

To meet the expectations of today's students and to serve them well, institutions need to capture the benefits offered by new technology and online instruction and embed best practices in their learning culture. Since faculty participation can neither be mandated nor fabricated, institutions must make online learning attractive, accessible, and valuable to faculty. Their engagement can evolve through a growing appreciation for the educational value of online learning that develops through personal experience — experience best acquired with guidance from knowledgeable and trusted colleagues.

Teams of instructional technology specialists, instructional designers, and education technologists are an important university asset. They work with faculty to overcome resistance to online learning, correct misperceptions, and help faculty create high-quality learning experiences with this important instructional medium. A talented instructional design team provides an effective bridge between the face-to-face instructional platform and a flipped, blended, online, or LMS-supported approach to learning that meets the needs of the increasingly diversified and geographically distributed student populations in higher education.

No comments:

Post a Comment